What does it mean to teach or coach sport for understanding?

In a games-based approach (GBA), the idea of understanding is located within the concept of games as decision-laden, problem solving contexts. However, the concept of ‘understanding’ is largely implicit in much of the germane literature. In GBAs there is a departure from the long persisting pedagogical idea of teaching as demonstrate-explain-practice (Tinning, 2010) and learner achievement of sport-as-techniques (Kirk, 2010; Landi, Fitzpatrick, & McGlashan, 2016; Light, 2013).GBAs assume a much ‘deeper’ knowledge, developed over time, occurs because of player reflection and agency not evident when the main teaching style is direct or 'command' instruction. GBAs provide an alternative to technical and mechanical (progressive part) notions of what players need to know and do to be ‘skilled players,’ but do they deliver on learning with understanding? It depends on what you mean by 'understanding'.

Almond (2010) recounted that GBAs emerged from educators’ concern with players, and young children particularly, not experiencing the ‘thrill’ of playing games. He proposed an additional pedagogical principle for game-based approaches: a pedagogy of engagement using the notion of ‘game sense’ as an important dimension of teaching games and sport for understanding. Almond suggested this would both enhance players understanding of games and their ability to appreciate their own potential to excite and be challenged (Almond, 2010). I suggest Almond may have been drawing attention to the potential of a GBA to be a pedagogical opportunity for more than the understanding of games as the development of intelligent decision-making at action during moments of play.

‘Understanding’ in the context of a game play can mean that a player is able to comprehend the logic of the game as a whole (Grehaigne, Richard & Griffin, 2005) and how that functions as tactical possibilities.Understanding might therefore be considered both an accomplishment and demonstrated ability (Almond & Ayres, 2013). While a GBA may present game information more adequately for learning from a constructivist and Gestalt psychological perspective, it might be considered that humans actively construct their own reality by organising meaning to create understanding. From this perspective, meaningful understanding means the individual operationalises what is learnt in the context of their preferred life (i.e. the understanding is ‘usable’; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). In a sense, meaning making is likely to be that which fosters the self-efficacy and habits of mind leading to the learned ability to arrange one's life in such a way that the physical activities they freely engage in make a distinctive contribution to their long-term flourishing (MacAllister, 2013). Meaningfulness is then characterised by how much the participant feels that experiences make sense and any related challenges associated with a task are worthy of committing to (Light & Harvey, 2017). Activities which have meaning encourage people to see challenges as being interesting, relevant and worthy of emotional commitment (Light & Harvey, 2017).

It has been suggested that humans see the world through the frame of meaning such that humans engage in activities they believe have overall value (Boser, 2017). It is the concept of meaning making that creates ‘value’ for the individual that attracts me to MacAllister’s (2013) definition of a physically educated person as one who has, “learned to arrange their lives in such a way that the physical activities they freely engage in makes a distinctive contribution to their long-term flourishing” (p. 908).This notion of movement freely engaged in for long term flourishing, or thriving, is how the wider value of games and sport can often be lost in an instrumental focus on sport through the sub parts of talent development, identification and recruitment, and competition. ‘Thriving’ and ‘flourishing’ are states of mind, a version or ‘story’ of one’s self, and games and sport have the potential to make a distinctive contribution to this version of one’s self by assisting understanding of one's self.

Over the last 30 years there is much research on the use of GBAs of many persuasions in teaching and coaching settings, including their limits, constraints, and possibilities for developing game ‘competent’ players, and exploration of supporting theories for the pedagogical tenets. I suggest investigating how the use of a GBA develops the habits of mind that lead to one choosing sport and games as activity choices throughout the life-course, and how sport and games develop the thinking and emotions associated with a sense of thriving in life, as the next frontier for GBA research and the development of teaching games for understanding.

This blog is adapted from sections of the paper:

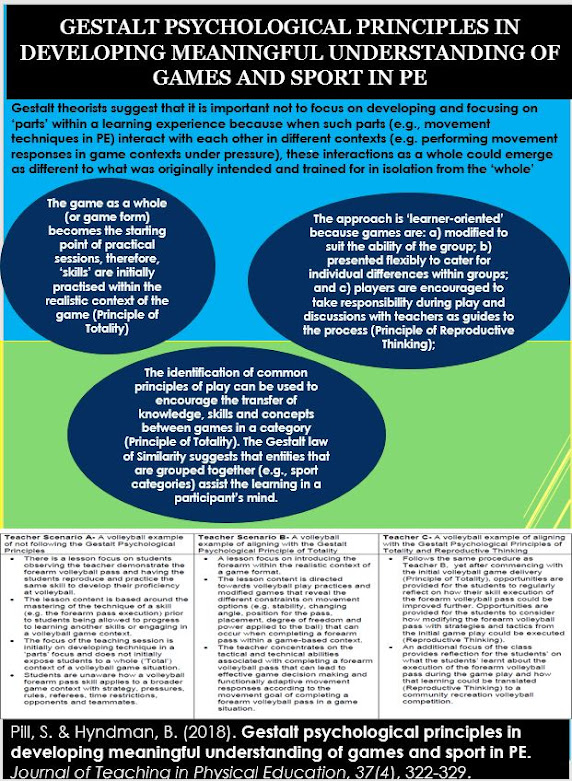

“Gestalt Psychological Principles in Developing Meaningful Understanding of Games and Sport in PE” by Pill S, Hyndman B. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. Available at

Thanks for stopping by and reading this blog. If you would like to connect with the ideas here or any of the ideas I have blogged about, you can contact via my email here

Comments

Post a Comment